Why is Slow Fashion So Slow to Catch On?

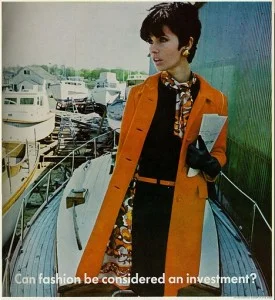

We’ve all been there before (or know someone who has): We’re strolling through our neighborhood mall and our eyes catch a glimpse of glossy signs inviting us to escape into a land of cotton and polyester. Dresses $8.99! Sweaters $9.99! Jeans $14.99! Once we step inside the brightly lit, chandeliered store, the mounds of perfectly folded garments, seductively postured manikins and catchy pop music have us hooked. Before we know it, we’re checking out at the register with a bag of reasonably priced clothes that we never planned on buying – and we’ve only spent $35. How can we resist?

For a generation of budget-conscious millennial shoppers, popping into stores like Forever 21, H&M, Uniqlo and Zara – that offer trendy clothes at low prices – has become par for the course. In 2013 alone, those four fast fashion retailers generated a combined $48 billion in global sales. And a recent report by the financial services firm Cowen Group forecasts that fast fashion sales will increase 11 percent year-over-year through 2020.

The realized growth in the fast fashion market has been astounding – and it’s leaving conventional apparel retailers in the dust. The traditional apparel model of selling seasonal lines of clothing, manufactured and marketed months in advance, has been replaced by these bargain brands that rapidly respond to the latest fashion trends and live by just-in-time production. As a whole, consumers have been loving it; yet, recent events have shed light on questionable aspects of fast fashion’s modus operandi that are prompting some consumers to think twice about purchasing those $5 T-shirts.

The collapse of an apparel-manufacturing factory in Bangladesh last year, which killed more than 1,100 workers, spurred a global conversation about human rights and fair labor practices of garment factory workers in international apparel supply chains. And an increased awareness of the intense water, energy and waste implications of apparel production – as well as health risks connected to endocrine disrupting and cancer-causing chemicals that have been found in clothes sold by 20 of the worlds top fashion brands – are also leading consumers to ask more questions about where their clothes come from and how they were made.

Queue in the slow fashion movement. For an industry that churns out fashions after fashions at the speed of consumers’ changing tastes, slow fashion is an oxymoron. Plain and simple, slow fashion promotes high quality versus fast production, durability versus design for obsolescence, and mindful consumption versus overconsumption.

Emerging designers and e-commerce innovators such as Zady, Modavanti and Cuyana are leading the movement, selling more ethically and sustainably made apparel that’s built to last.

“Fast-fashion is designed to fall apart after a few washes, so we as consumers go back to those brands to buy more and more. And as our closets fill with cheaply made clothing, our wallets start to empty out,” said Soraya Darabi, co-founder of Zady, a mission-driven brand best described as “The Whole Foods of Fashion.”

“A $5 dollar t-shirt may feel good initially, but that’s an empty high. When you work backwards to determine what a worker must have been paid to make such an inexpensively priced item, and you realize that that shirt will only last a few months before it falls to pieces and ends up on a landfill… second thoughts arise.”

Zady prides itself in selling women’s and men’s clothes and accessories that are not only beautiful and timeless, but are also made using the highest quality raw materials by ethically treated workers.

Responding to a rising consciousness among certain consumers, leading global apparel brands are also undergoing a slow fashion makeover that is intent on making clothes more sustainably.

The North Face, for example, recently launched an all-cotton hoodie that takes a cue from the slow food movement and brings a sustainably made garment from farm to closet. Called the Backyard Hoodie, the sweatshirt was grown, designed, cut and sewn within 150 miles of The North Face’s corporate headquarters in California using a slow fashion design approach. It is part of a line of products made in the United States using locally-sourced materials and resources, and designed to reduce waste.

Many other global apparel companies are increasingly committing to improve the environmental and social impact of their products and supply chains, too. Even fast fashion bastion H&M – the world’s second largest fashion retailer – has made sustainability commitments. Last year the Swedish retailer launched a Conscious Collection made from recycled fibers and organic cotton, and the company recently announced its commitment to pay living wages to textile workers in factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia. H&M hasn’t gone “slow,” but taking these steps is promising.

Despite rising tide of the slow fashion movement, the fact remains that slow fashion sales do not compare with those of fast fashion – in quantity or in dollars.

A look at example product prices may help explain why: An on-trend dress from a fast fashion retailer sells for $15.90, while a similar dress from a slow fashion site goes for $145; a fast fashion sweater is $24.90, and a slow fashion sweater is $160; fast fashion pants are $17.90, while slow fashion pants are $128. You get the picture.

Positioning slow fashion against fast fashion is like pitting David against Goliath. Of course, those low fast fashion prices do not accurately reflect the social and environmental costs of making those products. One would like to think that, given the choice, consumers would vote with their dollars and purchase high-quality, durable and ethical slow fashion products. But in a country still psychologically recovering from an economic recession, where the median annual household income is $54,000, it is no surprise which prices win out.

Indeed, fast fashion is a multi-billion dollar industry – and it’s growing. Fast fashion retailers have proliferated across the nation in the past decade and continue to cast their net. Case in point: Earlier this year, Forever 21 opened a concept test store called F21 Red, which boasts starting price points as low as $1.80 (selling $3.80 T-shirts, $5.80 leggings and $7.80 denim jeans). Already, Forever 21 operates 600 stores worldwide – and the company plans to double its global presence by 2017 – while Zara has 1,800 locations and H&M owns 3,400 stores. Both plan to amplify their global presence in coming years.

As H&M has shown, it is possible for fast fashion brands to move a little slower. Does that mean that someday those same brands will bring the slow fashion movement to the masses – and create a world where shoppers can feel good about purchasing accessibly-priced, ethically-made garments on the fly?

One can dream. For now, let’s hope that both fast and slow fashion brands can provide consumers with sufficient ethical and economical options to render their choices easier to make.